…I said that just as the American Jew is in political, economic, and cultural harmony with world Jewry, I was convinced that it was time for all Afro-Americans to join the world’s Pan-Africanists. I said that physically we Afro-Americans might remain in America, fighting for our Constitutional rights, but that philosophically and culturally we Afro-Americans badly needed to ‘return’ to Africa – and to develop a working unity in the framework of Pan-Africanism.” – Malcolm X (El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz)

Pan-Africanism as a movement or a series of movements; as a discipline; as an ideology and as a universal unification mechanism for the resurgence of solidarity amongst African peoples—both continental and in the Diaspora—even in its contemporary phase advocates the notions of Pan-African consolidation and the political, social, economic and even psychological independence for African peoples historically and currently under colonial and neo-colonial regimes.

In an attempt to insert the aggregation of cultural, spiritual, artistic, scientific and philosophical African presence and legacies in a pervasive European culture of dogmatism and racial fanaticism, Pan-Africanism and the ‘politicization’ of the Movement, was championed, most notably, by greats such as W.E.B. Du Bois, Kwame Nkrumah, Marcus Garvey, Jomo Kenyatta and countless others who pioneered and participated in the affairs of the Movement. On its historical continuum, the Pan-Africanism Movement was able to thrive as it spawned into a series of movements, during a time where racial injustice, discrimination and prejudice was considered to be at one of its peaks.

With its maturation into modernity, the pervasive and persistent nature of Pan-Africanism – as a discipline, as a series of movements and as a universal unification tool – has seemingly fallen by the wayside; as generations of those who survived and fought the flagrancy of racism for hope of a universal African confederation has shifted to generations of African-Americans/Blacks/Africans of the Diaspora birthed in the ideologies of racial subtlety, race progression and the fallacy that is color-blindness.

In a neoteric age where capitalism, individualism and the notions of post-racial society reigns supreme, Pan-Africanism in its contemporary phase, acts as more an educational and historical ideology of the past; rather than a revolutionary and progressive political movement applicable to both past and present endeavors of Black/African global consolidation.

This paper is not written to deny Pan-African political consciousness in contemporary U.S. society; nor is it written to refute that work is currently being done to advance the Pan-Africanism Movement within the Diaspora. What this paper proposes and investigates are some of the modern hindrances of the Pan-Africanism Movement in the United States and the roadblocks which are prohibiting the progressive fervor of the Movement; or rather what St. Clair Drake describes as “racial-Pan Africanism in the United States…through the Black Power Movement and its attempt to achieve the criterion of unity with continental Pan-Africanism. (Walters, 1993, p. 55) Though “African-Americans [have] been a dynamic element in generating movement toward a world-wide African unity” (Walters, 1993, p. 54), this papers aims to pose why 1) the political process of the Pan-Africanism Movement has halted in modernity and 2) the possible hindrances that have caused both an intercontinental and intra continental divide between African-Americans and Africans to push for Pan-African consolidation.

Though only but three to four hindrances will be addressed throughout this paper, the foundations of this research will serves as a blueprint for future analysis on the modern hindrances of Pan-Africanism in the 21st century. Therefore, by addressing these hindrances are only but an attempt to reawaken and rehabilitate the Movement that is Pan-Africanism.

The following hindrances will be addressed in this paper:

- African/African-American Stereotypes, Stigmas and Biases

- Africa as Sub-Saharan

- Inter-regional Integration/Cooperation (or lack thereof): The N.A.A.C.P and the African Union

- Barack Obama and the Myth of a Post-Racial Society

- African/African-American Stereotypes, Stigmas and Biases

Africa, as the world’s second largest and most populous continent, within itself comprises a spectrum of ethnicities, a range of histories, cultural expressions, peoples, lineages, languages and ancestral ties which accentuate the multifaceted and multifarious nature of the continent. Though this notion of Africa, as a diverse and heterogeneous entity may be obvious to some, the pervasive and perpetuated broadcasting of a one-dimensional Africa in the media has caused many to overlook the multifaceted nature of the continent. This ubiquitous transference of negative and one-dimensional imagery about Africa has not only survived from pre-colonial times but into modernity; its affects have caused both the Caucasian and the African-American alike to carry stigmas, stereotypes and biases about Africa.

Although these images of “helplessness, dependency and suffering may indeed be true”, (Mahadeo & McKinney, 2007) these notions are not representative of all the cultural space of Africa – but even with this concept, the highlighted imagery of Africa persists as it is widely disseminated. Here, the notion presented by Jo Ellen Fair, which states, “of all the world’s regions, Africa is the least understood by Americans” (Fair, 1993) can be applied; as “Africa and Africans have been invented historically and reinvented contemporarily.” (Fair, 1993) Stigmas and stereotypes of Africa and Africans such as “impoverished”, “famine-plague”, “full of war”, “jungle-covered”, “Aids-ridden”, “savage”, primitive”, “underdeveloped”, “tribal”, “corrupt” and “troubled” (Fair, 1993), have survived into modernity and have affected some African-Americans conscious outlook on Africa as a historical, cultural and contemporary space. Moreover, these stereotypes and stigmas are not only applicable or transferred by African-Americans but are also stigmas held by Africans about their intercontinental counterpart; as African-Americans are perceived by some Africans as ‘lazy’, ‘criminals’ or ‘without culture.’

In reference to Pan-Africanism, the stereotypes listed and the ideologies shared by African-Americans, Africans and even those within the Diaspora, pose as a modern hindrance to the Movement because these stanch ideologies and beliefs are rather proposed or favored over reinventing a formidable movement to contemporary Black solidification and unification. Though many members of the Movement in the 1960s faced similar “tensions between [the] two proud groups – Africans and African-Americans – in attempt in what St. Clair Drake describes as ‘groping’ (Walters, 1993, p.57), despite the cultural and societal differences, attempts and persistent thrusts to create and recognize Pan-Africanism as a political entity were made by several organizations such as the Organization of African Unity, the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee and the Pan-African Federation.

Although shared complexion does not automatically equate to racial solidarity, biases and stereotypes presents itself as a hindrance to contemporary Pan-Africanism as it can hinder Afro-centric political consciousness and formation in the Diaspora.

II. Africa as the Sub-Saharan

The saying, “science does not exist in a vacuum,” can also be applied to Africa, as Africa does not exist in a vacuum; as it is ever growing, changing and evolving. Africa, comprised of 54 states, including islands and various territories, can be seen as an entity within itself but comprised of various regions. In regards to Africa territories today, Africa has been dubbed with the pejorative jargon ‘sub-Saharan’; which is a colonialist term described as “an euphemism for contemptuousness employed by the continent’s detractors to delineate between the Arab countries that make up North Africa from the 42 countries and the islands that make-up the rest of Africa.” (Onyeani, 2009) By virtue of the term sub-Saharan, this means North Africa consists of Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco and Tunisia.

Here, sub-Saharan in regards to Pan-Africanism presents itself as a modern hindrance as it purports the notion of the reclamation of Africa to only consist of those who are ‘sub’ or ‘underneath’ the invisible border and not Africa as a whole. Sub-Saharan also excludes the “millions of indigenous Africans who are ethnic natives in Morocco, Algeria, Libya and Egypt.” (Onyeani, 2009) If Pan-Africanism enacts as not only as a unification but a liberatory mechanism from those under colonial rule in the Diaspora, even in its contemporary phase, should not be exclusionary of ‘Northern Africa’; but inclusionary of all Africa and the Diaspora.

‘Sub-Saharan Africa’, according to Owen ‘Alik’ Shahadah, is yet another racial construct. Shahadah writes:

“The notion of some invisible border, which divides the North of Africa from the South, is rooted in racism; which in part assumes that sand is an obstacle for African language and culture. This band of sand hence confines Africa to the bottom of a European imposed nation, which exists neither linguistically (Afro-Asiatic languages); ethnically (Tureg), politically (African Union, Arab League); economically (CEN-SAD) or physically (Sudan and Chad). The over-emphasis on sand as a defining feature in African history is grossly misleading, as culture, trade and languages do not stop when they meet geographic deserts. Thus, sub-Africa is another divisive vestige of colonial domination which balkanized Africa.” (Onyeani, 2009)

III. Inter-regional Integration/Cooperation (or lack thereof): The N.A.A.C.P and the African Union

Although representing different Africans/Blacks of the Diaspora on different continents and with specify of their aims in regards to their missions (with the mission of the National Association of the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is to “ensure the political, educational, social and economic equality of rights of all people to eliminate race-based discrimination”; and the African Union’s (AU) mission to be “an efficient and value-adding institution driving the African integration and development process in close collaboration with African Union Member States, the Regional Economic Communities and African citizens”) the NAACP and the African Union stand as pre-eminent organizations who were (and still are) crucial in advocating for the rights, liberties, justice and unification of Black/African peoples. (NAACP, 2013) (African Union, 2013)

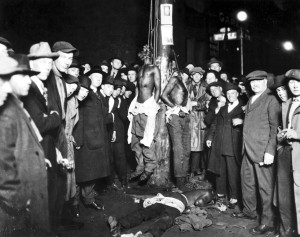

Birthed from the Race Riots of 1908, founded in 1909 after the Niagara Falls Movement (with the name of National Negro Committee) and finally in 1910 converting its name to the NAACP, the NAACP stands as the largest and oldest civil rights organization. Founded by white abolitionists and Black scholars who opposed the wretchedness of racial injustice, the pioneers of the movement include the likes of W.E.B. Du Bois, Ida B. Wells-Barnett and Mary Church Terrell. Contributions of the NAACP include the fight against the onslaught of Jim Crow and disenfranchisement, the creation of the Legal Defense Fund, civil suits against desegregation, lynching, media and federal advocacy, economic opportunity, health education and more.

The African Union, formerly known as the Organization of African Unity (O.A.U), was founded under a charter “institutionalizing the movement for African unity and was launched with the following aims: a) to promote the unity and solidarity of the African states b) to coordinate and intensify their cooperation and efforts c) to achieve better life for the peoples of Africa d) to defend their sovereignty, their territorial integrity and independence e) to eradicate all forms of colonialisms from Africa ad f) to promote international co-operation, having due regard to the Charter of the United Nations and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.” (Esedebe, 1982, pgs. 226-227)

In 1990, the O.A.U. shifted to the African Union and intensified their promotion of a regional integration perspective, as it advertised an “integrated, prosperous and peaceful Africa driven by its own citizens and representing a dynamic force in [the] global arena.” (Esedebe, 1982, p. 227) Consisting of 54 independent African states, the AU advocates ‘Pan-Africanism and the African Renaissance’, as it consists of a Pan-African Parliament and economic integration institutions such as the African Central Bank, the African Monetary Fund and the African Investment Bank.

Formidable in their own way on their perspective continents, both the NAACP and the African Union, present a modern hindrance to the Pan-Africanism Movement due to the lack of intercontinental integration, cooperation, organization and communication amongst the two groups. Although both groups advocate for the unification and the advancement of Black/African peoples, the NAACP and the AU focus on communal liberation, justice and unity for their respective domestic initiatives, issues and socio-economic and political values. But , I also argue that they also enact as individualistic entities; as they only focus on endeavors ranging on the interests of their continent and not the interests of Pan-Africanism within the Diaspora.

For example, one of the AU’s objectives is to “work with relevant international partners…in the eradication of preventable diseases and the promotion of good health on the continent.” (The African Union, 2013) Their many ‘continent-to-continent’ partnerships include Afro-Arab cooperation; the African-European Union partnership; the Africa-South America summits; and the Africa-Asia Sub-Regional Organizations Conference (AASROC). Their ‘continent-to-country partnerships’ also include India, Turkey, China, France and Korea; with prospective partnerships with the Caribbean, Iran and Australasia. Although the AU has the African-Growth Opportunity Act (AGOA) with the United States, which “offers tangible initiative for African countries to continue their efforts to open their economies and build-free markets”, no other connections or partnerships has been fortified with Black organizations in the Diaspora, including America. This notion includes the N.A.A.C.P., as it too in its contemporary phase, has lacked to connect or re-connect with African organizations such as the AU.

This proves to be a hindrance in the modern Pan-Africanism Movement in the Diaspora as organizations such as the AU and the NAACP only emphasize their individual African/Black issues; thus, excluding African/Black representation, consolidation and unity as an option.

This is why in July of 1964, Malcolm X (El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz) told an O.A.U summit:

“We in America, are your host brothers and sisters, and I am only to remind you that your problems are our problems. As the African-Americans “awaken” today, we find ourselves in a strange land that has rejected us, and, like the prodigal son we are turning to our elder brothers for help. We pray our pleas do not fall upon deaf ears…

Your problems will never be solved until and unless ours are solved. You will never be fully respected unless we are also respected. You will never be recognized as free human beings until and unless we are also recognized and treated as human beings.”

(Esedebe, 1982, p. 233) (The African Union: A United and Strong Africa ) (Fair, 1993) (Onyeani, 2009 )

IV. Barack Obama and the Myth of a Post-Racial Society

The election of 44th President of the United States, Barack Obama, as the first African-American President, was not only a pivotal turning point in the history of the United States but it also ushered a new wave of politics; as many believed that the election of the first Black President in a American society (known for its paradigm of blatant racism, cruel prejudice and wretched bigotry) changed the landscape of race-relations in the United States of America.

Thus, this notion of a new political terrain, supposedly ‘unnerved and unscathed’ by race, has caused many Americans to believe in thoughts of the possibilities of a multi-democracy and the idea that America is now embarking towards becoming a ‘post-racial society.’

According to Cathy J. Cohen, author of “Millenials and the Myth of the Post-Racial Society: Black Youth, Intra-generational Divisions and the Continuing Racial Divide in American Politics”, with this notion of a post-racial/multi-democracy society, some academics and journalist purport that “once millenials dominate the political arena, many of the thorny social issues that have caused a great debate and consternation among the American public will be resolved.” (Cohen, 2011) Cohen also writes that “this line of reasoning suggests that young people who embrace and personify a more inclusive society will eventually take over both policy-making and thought leadership, moving both in a more liberal direction.” (Cohen, 2011)

Although many minority youth reject or are “particularly suspicious of a post-racial anything” (Cohen, 2011) another truth emerges where many youth are not suspicious of the notion of a post-racial society; not only based on the election of President Obama but also based on the ‘lack’ of consistency of the onslaught of racism, the common acceptance of racial subtlety and race-relations as progressive.

The notions of a post-racial society as an ideology amongst the youth –specifically, Black youth—presents itself as a hindrance to Pan-Africanism as it disrupts the notion of a need for a current and contemporary age of Black/African consolidation. If Pan-Africanism in its emerging stages, as an idea and as movement, was sparked by the consciousness of Black/African youth to the degradation and the ill-treatment of Blacks within the Diaspora, how will the movement re-ignite itself in a society where the notions of Pan-Africa are only but an idea of the past and not needed for current and future endeavors?

V. Conclusion

Although four hindrances were discussed throughout this paper— 1) African/African-American Stereotypes, Stigmas and Biases 2) Africa as Sub-Saharan 3) Inter-regional Integration/Cooperation (or lack thereof): The N.A.A.C.P and the African Union and 4) Barack Obama and the Myth of a Post-Racial Society, the foundations of this research will serves as a blueprint for future analysis on the modern hindrances of Pan-Africanism in the 21st century. Therefore, by addressing these hindrances are only but an attempt to reawaken and rehabilitate the Movement that is Pan-Africanism.

Sources:

Cohen, C. J. (2011). Millenials & the Myth of the Post-Racial Society: Black Youth, Intra-generational Divisions and the Continuing Racial Divide in American Politics. 140, pp. 197-205.

Esedebe, O. P. Pan-Africanism: The Idea and Movement 1776-1963. District of Columbia , Washington , 1982: Howard University Press .

Fair, J. E. (1993). War, Famine and Poverty: Race in the Construction of Africa’s Media Image . Journal of Communication Inquiry , 5-22.

Mahadeo, M. &. (2007 ). Media representations of Africa: Still the same old story? (Vol. 4). Policy & Practice: A Development Education Review.

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People . (n.d.). Retrieved from NAACP: http://www.naacp.org

Onyeani, C. (2009 ). Contemptuousness of ‘Sub-Saharan Africa. Retrieved from African News World: The #1 News about Africa: www.africannewsworld.com/2009/07/contemptuousness-of-sub-saharan-africa.html

The African Union: A United and Strong Africa . (n.d.). (T. A. Commission, Producer) Retrieved from http://www.au/int/en/

Walters, R. W. (1993). Pan-Africanism in the African Diaspora . Detroit , Michigan , United States of America: Wayne State University Press .